8. Open Rails Physics¶

Open Rails physics is in an advanced stage of development. The physics

structure is divided into logical classes; more generic classes are parent

classes, more specialized classes inherit properties and methods of their

parent class. Therefore, the description for train cars physics is also

valid for locomotives (because a locomotive is a special case of a train

car). All parameters are defined within the .wag or .eng file. The

definition is based on MSTS file format and some additional ORTS based

parameters. To avoid possible conflicts in MSTS, the ORTS prefix is

added to every OpenRails specific parameter (such as

ORTSMaxTractiveForceCurves).

The .wag or .eng file may be placed as in MSTS in the

TRAINS\TRAINSET\TrainCar\ folder (where TrainCar is the name of the

train car folder). If OR-specific parameters are used, or if different

.wag or .eng files are used for MSTS and OR, the preferred solution is to

place the OR-specific .wag or .eng file in a created folder

TRAINS\TRAINSET\TrainCar\OpenRails\ (see here

for more).

8.1. Train Cars (WAG, or Wagon Part of ENG file)¶

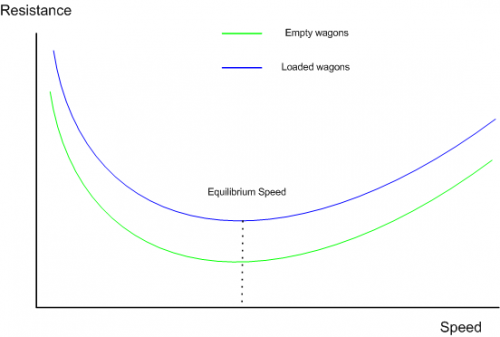

The behavior of a train car is mainly defined by a resistance / resistive force (a force needed to pull a car). Train car physics also includes coupler slack and braking. In the description below, the Wagon section of the WAG / ENG file is discussed.

8.1.1. Resistive Forces¶

Open Rails physics calculates resistance based on real world physics: gravity, mass, rolling resistance and optionally curve resistance. This is calculated individually for each car in the train. The program calculates rolling resistance, or friction, based on the Friction parameters in the Wagon section of .wag/.eng file. Open Rails identifies whether the .wag file uses the FCalc utility or other friction data. If FCalc was used to determine the Friction variables within the .wag file, Open Rails compares that data to the Open Rails Davis equations to identify the closest match with the Open Rails Davis equation. If no-FCalc Friction parameters are used in the .wag file, Open Rails ignores those values, substituting its actual Davis equation values for the train car.

A basic (simplified) Davis formula is used in the following form:

Fres = ORTSDavis_A + speedMpS * (ORTSDavis_B + ORTSDavis_C * speedMpS2)

Where Fres is the friction force of the car. The rolling resistance can be defined either by FCalc or ORTSDavis_A, _B and _C components. If one of the ORTSDavis components is zero, FCalc is used. Therefore, e.g. if the data doesn’t contain the B part of the Davis formula, a very small number should be used instead of zero.

When a car is pulled from steady state, an additional force is needed due to higher bearing forces. The situation is simplified by using a different calculation at low speed (5 mph and lower). Empirical static friction forces are used for different classes of mass (under 10 tons, 10 to 100 tons and above 100 tons). In addition, if weather conditions are poor (snowing is set), the static friction is increased.

When running on a curve and if the

Curve dependent resistance option is

enabled, additional resistance is calculated, based on the curve radius,

rigid wheel base, track gauge and super elevation. The curve resistance

has its lowest value at the curve’s optimal speed. Running at higher or

lower speed causes higher curve resistance. The worst situation is

starting a train from zero speed. The track gauge value can be set by

ORTSTrackGauge parameter, otherwise 1435 mm is used. The rigid wheel base

can be also set by ORTSRigidWheelBase, otherwise the value is estimated.

Further details are discussed later.

When running on a slope (uphill or downhill), additional resistance is

calculated based on the car mass taking into account the elevation of the

car itself. Interaction with the car vibration feature is a known issue

(if the car vibrates the resistance value oscillate).

8.1.2. Coupler Slack¶

Slack action for couplers is introduced and calculated the same way as in MSTS.

8.1.3. Adhesion of Locomotives – Settings Within the Wagon Section of ENG files¶

MSTS calculates the adhesion parameters based on a very strange set of parameters filled with an even stranger range of values. Since ORTS is not able to mimic the MSTS calculation, a standard method based on the adhesion theory is used with some known issues in use with MSTS content.

MSTS Adheasion (sic!) parameters are not used in ORTS. Instead, a new

set of parameters is used, which must be inserted within the Wagon

section of the .ENG file:

ORTSAdhesion (

ORTSCurtius_Kniffler (A B C D )

)

The A, B and C values are coefficients of a standard form of various empirical formulas, e.g. Curtius-Kniffler or Kother. The D parameter is used in the advanced adhesion model described later.

From A, B and C a coefficient CK is computed, and the adhesion force limit is then calculated by multiplication of CK by the car mass and the acceleration of gravity (9.81), as better explained later.

The adhesion limit is only considered in the adhesion model of locomotives.

The adhesion model is calculated in two possible ways. The first one – the simple adhesion model – is based on a very simple threshold condition and works similarly to the MSTS adhesion model. The second one – the advanced adhesion model – is a dynamic model simulating the real world conditions on a wheel-to-rail contact and will be described later. The advanced adhesion model uses some additional parameters such as:

ORTSAdhesion (

ORTSSlipWarningThreshold ( T )

)

where T is the wheelslip percentage considered as a warning value to be displayed to the driver; and:

ORTSAdhesion(

Wheelset (

Axle (

ORTSInertia (

Inertia

)

)

)

)

where Inertia is the model inertia in kg.m2 and can be set to adjust the advanced adhesion model dynamics. The value considers the inertia of all the axles and traction drives. If not set, the value is estimated from the locomotive mass and maximal power.

The first model – simple adhesion model – is a simple tractive force condition-based computation. If the tractive force reaches its actual maximum, the wheel slip is indicated in HUD view and the tractive force falls to 10% of the previous value. By reducing the throttle setting adherence is regained. This is called the simple adhesion model.

The second adhesion model (advanced adhesion model) is based on a simplified dynamic adhesion theory. Very briefly, there is always some speed difference between the wheel speed of the locomotive and the longitudinal train speed when the tractive force is different from zero. This difference is called wheel slip / wheel creep. The adhesion status is indicated in the HUD Force Information view by the Wheel Slip parameter and as a warning in the general area of the HUD view. For simplicity, only one axle model is computed (and animated). A tilting feature and the independent axle adhesion model will be introduced in the future.

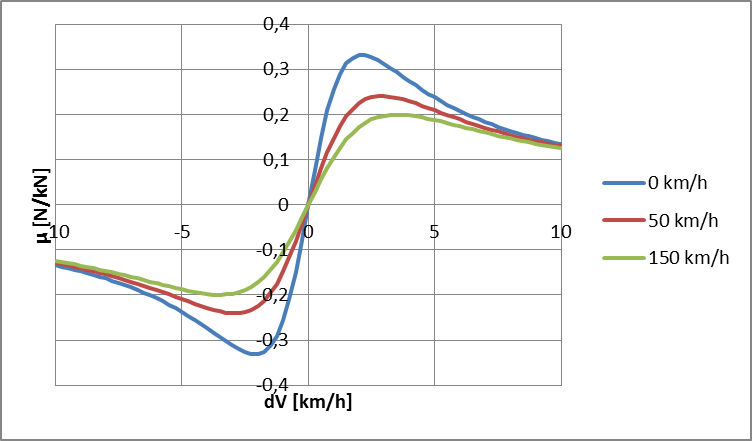

The heart of the model is the slip characteristics (picture below).

The wheel creep describes the stable area of the characteristics and is used in the most of the operation time. When the tractive force reaches the actual maximum of the slip characteristics, force transition falls down and more power is used to speed up the wheels, so called wheel slip.

To avoid the loss of the tractive force, use the throttle in combination

with sanding to return to the stable area (wheel creep area). A possible

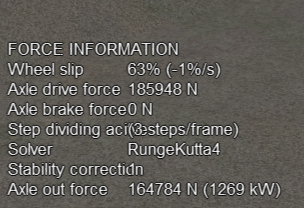

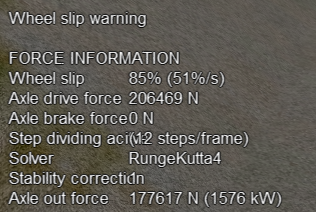

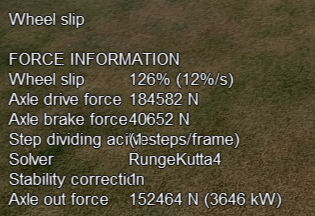

sequence of the wheel slip development is shown on the pictures below. The

Wheel slip value is displayed as a value relative to the best adhesion

conditions for actual speed and weather. The value of 63% means very good

force transition. For values higher than ( ORTSadhesion (

ORTSSlipWarningThreshold ) ) or 70% by default, the Wheel slip

warning is displayed, but the force transition is still very good. This

indication should warn you to use the throttle very carefully. Exceeding

100%, the Wheel slip message is displayed and the wheels are starting

to speed up, which can be seen on the speedometer or in external view 2.

To reduce the wheel slip, use throttle down, sanding or the locomotive

brake.

The actual maximum of the tractive force is based on the

Curtius-Kniffler adhesion theory and can be adjusted by the aforementioned

ORTSCurtius_Kniffler ( A B C D ) parameters, where A, B, C are

coefficients of Curtius-Kniffler, Kother or similar formula. By default,

Curtius-Kniffler is used.

Where W is the weather coefficient. This means that the maximum is

related to the speed of the train, or to the weather conditions.

The D parameter is used in an advanced adhesion model and should

always be 0.7.

There are some additional parameters in the Force Information HUD view. The axle/wheel is driven by the Axle drive force and braked by the Axle brake force. The Axle out force is the output force of the adhesion model (used to pull the train). To compute the model correctly the FPS rate needs to be divided by a Solver dividing value in a range from 1 to 50. By default, the Runge-Kutta4 solver is used to obtain the best results. When the Solver dividing value is higher than 40, in order to reduce CPU load the Euler-modified solver is used instead.

In some cases when the CPU load is high, the time step for the computation

may become very high and the simulation may start to oscillate (the

Wheel slip rate of change (in the brackets) becomes very high). There

is a stability correction feature that modifies the dynamics of the

adhesion characteristics. Higher instability can cause a huge wheel slip.

You can use the DebugResetWheelSlip (<Ctrl+X> keys by default)

command to reset the adhesion model. If you experience such behavior most

of time, use the basic adhesion model instead by pressing

DebugToggleAdvancedAdhesion ( <Ctrl+Alt+X> keys by default).

Another option is to use a Moving average filter available in the Simulation Options. The higher the value, the more stable the simulation will be. However, the higher value causes slower dynamic response. The recommended range is between 10 and 50.

To match some of the real world features, the Wheel slip event can

cause automatic zero throttle setting. Use the Engine (ORTS

(ORTSWheelSlipCausesThrottleDown)) Boolean value of the ENG file.

8.2. Engine – Classes of Motive Power¶

Open Rails software provides for different classes of engines: diesel, electric, steam and default. If needed, additional classes can be created with unique performance characteristics.

8.2.1. Diesel Locomotives in General¶

The diesel locomotive model in ORTS simulates the behavior of two basic

types of diesel engine driven locomotives– diesel-electric and

diesel-mechanical. The diesel engine model is the same for both types, but

acts differently because of the different type of load. Basic controls

(direction, throttle, dynamic brake, air brakes) are common across all

classes of engines. Diesel engines can be started or stopped by pressing

the START/STOP key (<Shift+Y> in English keyboards). The starting and

stopping sequence is driven by a starter logic, which can be customized,

or is estimated by the engine parameters.

8.2.1.1. Starting the Diesel Engine¶

To start the engine, simply press the START/STOP key once. The direction controller must be in the neutral position (otherwise, a warning message pops up). The engine RPM (revolutions per minute) will increase according to its speed curve parameters (described later). When the RPM reaches 90% of StartingRPM (67% of IdleRPM by default), the fuel starts to flow and the exhaust emission starts as well. RPM continues to increase up to StartingConfirmationRPM (110% of IdleRPM by default) and the demanded RPM is set to idle. The engine is now started and ready to operate.

8.2.1.2. Stopping the Diesel Engine¶

To stop the engine, press the START/STOP key once. The direction controller must be in the neutral position (otherwise, a warning message pops up). The fuel flow is cut off and the RPM will start to decrease according to its speed curve parameters. The engine is considered as fully stopped when RPM is zero. The engine can be restarted even while it is stopping (RPM is not zero).

8.2.1.3. Starting or Stopping Helper Diesel Engines¶

By pressing the Diesel helper START/STOP key (<Ctrl+Y> on English

keyboards), the diesel engines of helper locomotives can be started or

stopped. Also consider disconnecting the unit from the multiple-unit (MU)

signals instead of stopping the engine

(see here, Toggle MU connection).

It is also possible to operate a locomotive with the own engine off and the helper’s engine on.

8.2.1.4. ORTS Specific Diesel Engine Definition¶

If no ORTS specific definition is found, a single diesel engine definition is created based on the MSTS settings. Since MSTS introduces a model without any data crosscheck, the behavior of MSTS and ORTS diesel locomotives can be very different. In MSTS, MaxPower is not considered in the same way and you can get much better performance than expected. In ORTS, diesel engines cannot be overloaded.

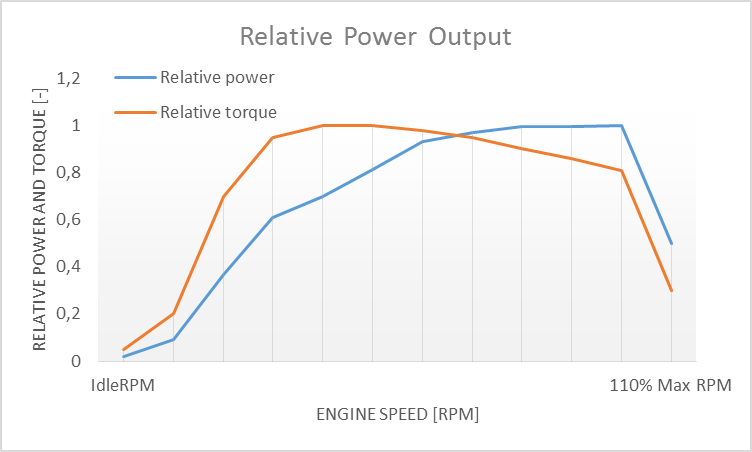

No matter which engine definition is used, the diesel engine is defined by its load characteristics (maximum output power vs. speed) for optimal fuel flow and/or mechanical characteristics (output torque vs. speed) for maximum fuel flow. The model computes output power / torque according to these characteristics and the throttle settings. If the characteristics are not defined (as they are in the example below), they are calculated based on the MSTS data and common normalized characteristics.

In many cases the throttle vs. speed curve is customized because power vs. speed is not linear. A default linear throttle vs. speed characteristics is built in to avoid engine overloading at lower throttle settings. Nevertheless, it is recommended to adjust the table below to get more realistic behavior.

In ORTS, single or multiple engines can be set for one locomotive. In case

there is more than one engine, other engines act like helper engines

(start/stop control for helpers is <Ctrl+Y> by default). The power of

each active engine is added to the locomotive power. The number of such

diesel engines is not limited.

If the ORTS specific definition is used, each parameter is tracked and if one is missing (except in the case of those marked with Optional), the simulation falls back to use MSTS parameters.

Engine(

...

ORTSDieselEngines ( 2

Diesel (

IdleRPM ( 510 )

MaxRPM ( 1250 )

StartingRPM ( 400 )

StartingConfirmRPM ( 570 )

ChangeUpRPMpS ( 50 )

ChangeDownRPMpS ( 20 )

RateOfChangeUpRPMpSS ( 5 )

RateOfChangeDownRPMpSS ( 5 )

MaximalPower ( 300kW )

IdleExhaust ( 5 )

MaxExhaust ( 50 )

ExhaustDynamics ( 10 )

ExhaustDynamicsDown (10)

ExhaustColor ( 00 fe )

ExhaustTransientColor(

00 00 00 00)

DieselPowerTab (

0 0

510 2000

520 5000

600 2000

800 70000

1000 100000

1100 200000

1200 280000

1250 300000

)

DieselConsumptionTab (

0 0

510 10

1250 245

)

ThrottleRPMTab (

0 510

5 520

10 600

20 700

50 1000

75 1200

100 1250

)

DieselTorqueTab (

0 0

510 25000

1250 200000

)

MinOilPressure ( 40 )

MaxOilPressure ( 90 )

MaxTemperature ( 120 )

Cooling ( 3 )

TempTimeConstant ( 720 )

OptTemperature ( 90 )

IdleTemperature ( 70 )

)

Diesel ( ... )

|

Engine section in eng file

Number of engines

Idle RPM

Maximal RPM

Starting RPM

Starting confirmation RPM

Increasing change rate RPM/s

Decreasing change rate RPM/s

Jerk of ChangeUpRPMpS RPM/s^2

Jerk of ChangeDownRPMpS RPM/s^2

Maximal output power

Num of exhaust particles at IdleRPM

Num of exhaust particles at MaxRPM

Exhaust particle mult. at transient

Mult. for down transient (Optional)

Exhaust color at steady state

Exhaust color at RPM changing

Diesel engine power table

RPM Power in Watts

Diesel fuel consumption table

RPM Vs consumption l/h/rpm

Eengine RPM vs. throttle table

Throttle % Demanded RPM

Diesel engine RPM vs. torque table

RPM Force in Newtons

Min oil pressure PSI

Max oil pressure PSI

Maximal temperature Celsius

Cooling 0=No cooling, 1=Mechanical,

2= Hysteresis, 3=Proportional

Rate of temperature change

Normal temperature Celsius

Idle temperature Celsius

The same as above, or different

|

8.2.1.5. Diesel Engine Speed Behavior¶

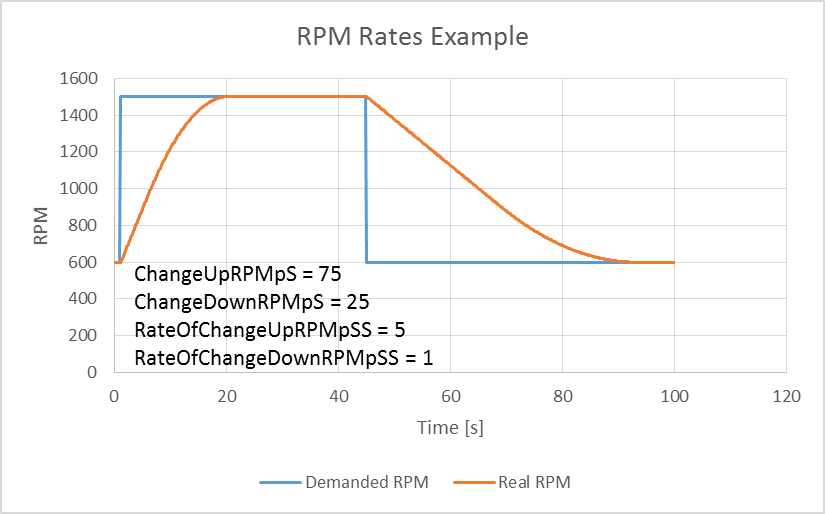

The engine speed is calculated based on the RPM rate of change and its

rate of change. The usual setting and the corresponding result is shown

below. ChangeUpRPMpS means the slope of RPM, RateOfChangeUpRPMpSS

means how fast the RPM approaches the demanded RPM.

8.2.1.6. Fuel Consumption¶

Following the MSTS model, ORTS computes the diesel engine fuel consumption based on .eng file parameters. The fuel flow and level are indicated by the HUD view. Final fuel consumption is adjusted according to the current diesel power output (load).

8.2.1.7. Diesel Exhaust¶

The diesel engine exhaust feature can be modified as needed. The main idea

of this feature is based on the general combustion engine exhaust. When

operating in a steady state, the color of the exhaust is given by the new

ENG parameter engine (ORTS (Diesel (ExhaustColor))).

The amount of particles emitted is given by a linear interpolation of the

values of engine(ORTS (Diesel (IdleExhaust))) and engine(ORTS (Diesel

(MaxExhaust))) in the range from 1 to 50. In a transient state, the

amount of the fuel increases but the combustion is not optimal. Thus, the

quantity of particles is temporarily higher: e.g. multiplied by the value

of

engine(ORTS (Diesel (ExhaustDynamics))) and displayed with the color

given by engine(ORTS(Diesel(ExhaustTransientColor))).

The format of the color value is (aarrggbb) where:

- aa = intensity of light;

- rr = red color component;

- gg = green color component;

- bb = blue color component;

and each component is in HEX number format (00 to ff).

8.2.1.8. Cooling System¶

ORTS introduces a simple cooling and oil system within the diesel engine model. The engine temperature is based on the output power and the cooling system output. A maximum value of 100°C can be reached with no impact on performance. It is just an indicator, but the impact on the engine’s performance will be implemented later. The oil pressure feature is simplified and the value is proportional to the RPM. There will be further improvements of the system later.

8.2.2. Diesel-Electric Locomotives¶

Diesel-electric locomotives are driven by electric traction motors supplied by a diesel-generator set. The gen-set is the only power source available, thus the diesel engine power also supplies auxiliaries and other loads. Therefore, the output power will always be lower than the diesel engine rated power.

In ORTS, the diesel-electric locomotive can use

ORTSTractionCharacteristics or tables of ORTSMaxTractiveForceCurves

to provide a better approximation to real world performance. If a table is

not used, the tractive force is limited by MaxForce, MaxPower and

MaxVelocity. The throttle setting is passed to the ThrottleRPMTab, where

the RPM demand is selected. The output force increases with the Throttle

setting, but the power follows maximal output power available (RPM

dependent).

8.2.3. Diesel-Hydraulic Locomotives¶

Diesel-hydraulic locomotives are not implemented in ORTS. However, by

using either ORTSTractionCharacteristics or ORTSMaxTractiveForceCurves

tables, the desired performance can be achieved, when no gearbox is in use

and the DieselEngineType is electric.

8.2.4. Diesel-Mechanical Locomotives¶

ORTS features a mechanical gearbox feature that mimics MSTS behavior,

including automatic or manual shifting. Some features not well described

in MSTS are not yet implemented, such as GearBoxBackLoadForce,

GearBoxCoastingForce and GearBoxEngineBraking.

Output performance is very different compared with MSTS. The output force is computed using the diesel engine torque characteristics to get results that are more precise.

8.3. Electric Locomotives¶

At the present time, diesel and electric locomotive physics calculations use the default engine physics. Default engine physics simply uses the MaxPower and MaxForce parameters to determine the pulling power of the engine, modified by the Reverser and Throttle positions. The locomotive physics can be replaced by traction characteristics (speed in mps vs. force in Newtons) as described below.

Some OR-specific parameters are available in order to improve the realism of the electric system.

8.3.1. Pantographs¶

The pantographs of all locomotives in a consist are triggered by

Control Pantograph First and Control Pantograph Second commands

( <P> and <Shift+P> by default ). The status of the pantographs

is indicated by the Pantographs value in the HUD view.

Since the simulator does not know whether the pantograph in the 3D model is up or down, you can set some additional parameters in order to add a delay between the time when the command to raise the pantograph is given and when the pantograph is actually up.

In order to do this, you can write in the Wagon section of your .eng file or .wag file (since the pantograph may be on a wagon) this optional structure:

ORTSPantographs(

Pantograph( << This is going to be your first pantograph.

Delay( 5s ) << Example : a delay of 5 seconds

)

Pantograph(

... parameters for the second pantograph ...

)

)

Other parameters will be added to this structure later, such as power limitations or speed restrictions.

8.3.2. Circuit breaker¶

The circuit breaker of all locomotives in a consist can be controlled by

Control Circuit Breaker Closing Order, Control Circuit Breaker Opening Order

and Control Circuit Breaker Closing Authorization commands

( <O>, <I> and <Shift+O> by default ). The status of the circuit breaker

is indicated by the Circuit breaker value in the HUD view.

Two default behaviours are available:

- By default, the circuit breaker of the train closes as soon as power is available on the pantograph.

- The circuit breaker can also be controlled manually by the driver. To get this

behaviour, put the parameter

ORTSCircuitBreaker( Manual )in the Engine section of the ENG file.

In order to model a different behaviour of the circuit breaker,

a scripting interface is available. The script can be loaded with the

parameter ORTSCircuitBreaker( <name of the file> ).

In real life, the circuit breaker does not

close instantly, so you can add a delay with the optional parameter

ORTSCircuitBreakerClosingDelay( ) (by default in seconds).

8.3.3. Power supply¶

The power status is indicated by the Power value in the HUD view.

The power-on sequence time delay can be adjusted by the optional

ORTSPowerOnDelay( ) value (for example: ORTSPowerOnDelay( 5s )) within

the Engine section of the .eng file (value in seconds). The same delay for

auxiliary systems can be adjusted by the optional parameter

ORTSAuxPowerOnDelay( ) (by default in seconds).

8.4. Steam Locomotives¶

8.4.1. General Introduction to Steam Locomotives¶

8.4.1.1. Principles of Train Movement¶

Key Points to Remember:

- Steam locomotive tractive effort must be greater than the train resistance forces.

- Train resistance is impacted by the train itself, curves, gradients, tunnels, etc.

- Tractive effort reduces with speed, and will reach a point where it equals the train resistance, and thus the train will not be able to go any faster.

- This point will vary as the train resistance varies due to changing track conditions.

- Theoretical tractive effort is determined by the boiler pressure, cylinder size, drive wheel diameters, and will vary between locomotives.

- Low Factors of Adhesion will cause the locomotive’s driving wheels to slip.

8.4.1.1.1. Forces Impacting Train Movement¶

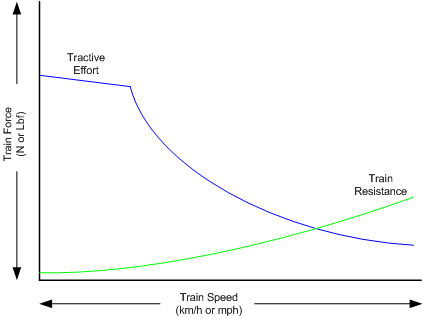

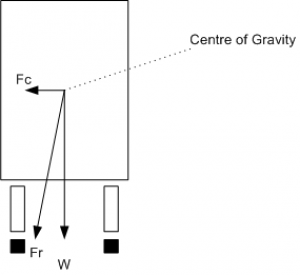

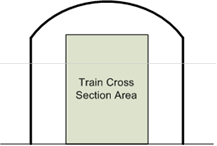

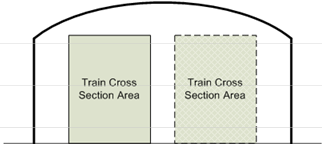

The steam locomotive is a heat engine which converts heat energy generated through the burning of fuel, such as coal, into heat and ultimately steam. The steam is then used to do work by injecting the steam into the cylinders to drive the wheels around and move the locomotive forward. To understand how a train will move forward, it is necessary to understand the principal mechanical forces acting on the train. The diagram below shows the two key forces affecting the ability of a train to move.

The first force is the tractive effort produced by the locomotive, whilst the second force is the resistance presented by the train. Whenever the tractive effort is greater than the train resistance the train will continue to move forward; once the resistance exceeds the tractive effort, then the train will start to slow down, and eventually will stop moving forward.

The sections below describe in more detail the forces of tractive effort and train resistance.

8.4.1.1.2. Train Resistance¶

The movement of the train is opposed by a number of different forces which are collectively grouped together to form the train resistance.

The main resistive forces are as follows (the first two values of resistance are modelled through the Davis formulas, and only apply on straight level track):

- Journal or Bearing resistance (or friction)

- Air resistance

- Gradient resistance – trains travelling up hills will experience greater resistive forces then those operating on level track.

- Curve resistance – applies when the train is traveling around a curve, and will be impacted by the curve radius, speed, and fixed wheel base of the rolling stock.

- Tunnel resistance – applies when a train is travelling through a tunnel.

8.4.1.1.3. Tractive Effort¶

Tractive Effort is created by the action of the steam against the pistons, which, through the media of rods, crossheads, etc., cause the wheels to revolve and the engine to advance.

Tractive Effort is a function of mean effective pressure of the steam cylinder and is expressed by following formula for a simple locomotive. Geared and compound locomotives will have slightly different formula:

TE = Cyl/2 x (M.E.P. x d2 x s) / D

Where:

- Cyl = number of cylinders

- TE = Tractive Effort (lbf)

- M.E.P. = mean effective pressure of cylinder (psi)

- D = diameter of cylinder (in)

- S = stroke of cylinder piston (in)

- D = diameter of drive wheels (in)

8.4.1.1.4. Theoretical Tractive Effort¶

To allow the comparison of different locomotives, as well as determining their relative pulling ability, a theoretical approximate value of tractive effort is calculated using the boiler gauge pressure and includes a factor to reduce the value of M.E.P.

Thus our formula from above becomes:

TE = Cyl/2 x (0.85 x BP x d2 x s) / D

Where:

- BP = Boiler Pressure (gauge pressure - psi)

- 0.85 – factor to account for losses in the engine, typically values between 0.7 and 0.85 were used by different manufacturers and railway companies.

8.4.1.1.5. Factor of Adhesion¶

The factor of adhesion describes the likelihood of the locomotive slipping when force is applied to the wheels and rails, and is the ratio of the starting Tractive Effort to the weight on the driving wheels of the locomotive:

FoA = Wd / TE

Where:

- FoA = Factor of Adhesion

- TE = Tractive Effort (lbs)

- Wd = Weight on Driving Wheels (lbs)

Typically the Factor of Adhesion should ideally be between 4.0 & 5.0 for steam locomotives. Values below this range will typically result in slippage on the rail.

8.4.1.1.6. Indicated HorsePower (IHP)¶

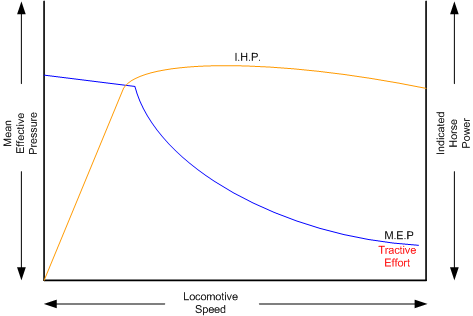

Indicated Horsepower is the theoretical power produced by a steam locomotive. The generally accepted formula for Indicated Horsepower is:

I.H.P. = Cyl/2 x (M.E.P. x L x A x N) / 33000

Where:

- IHP = Indicated Horsepower (hp)

- Cyl = number of cylinders

- M.E.P. = mean effective pressure of cylinder (psi)

- L = stroke of cylinder piston (ft)

- A = area of cylinder (sq in)

- N = number of cylinder piston strokes per min (NB: two piston strokes for every wheel revolution)

As shown in the diagram below, IHP increases with speed, until it reaches a maximum value. This value is determined by the cylinder’s ability to maintain an efficient throughput of steam, as well as for the boiler’s ability to maintain sufficient steam generation to match the steam usage by the cylinders.

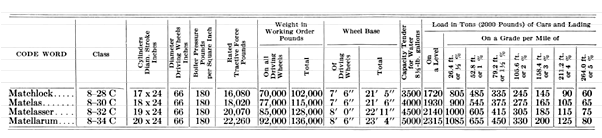

8.4.1.1.7. Hauling Capacity of Locomotives¶

Thus it can be seen that the hauling capacity is determined by the summation of the tractive effort and the train resistance.

Different locomotives were designed to produce different values of tractive effort, and therefore the loads that they were able to haul would be determined by the track conditions, principally the ruling gradient for the section, and the load or train weight. Therefore most railway companies and locomotive manufacturers developed load tables for the different locomotives depending upon their theoretical tractive efforts.

The table below is a sample showing the hauling capacity of an American (4-4-0) locomotive from the Baldwin Locomotive Company catalogue, listing the relative loads on level track and other grades as the cylinder size, drive wheel diameter, and weight of the locomotive is varied.

Typically the ruling gradient is defined as the maximum uphill grade facing a train in a particular section of the route, and this grade would typically determine the maximum permissible load that the train could haul in this section. The permissible load would vary depending upon the direction of travel of the train.

8.4.1.2. Elements of Steam Locomotive Operation¶

A steam locomotive is a very complex piece of machinery that has many component parts, each of which will influence the performance of the locomotive in different ways. Even at the peak of its development in the middle of the 20th century, the locomotive designer had at their disposal only a series of factors and simple formulae to describe its performance. Once designed and built, the performance of the locomotive was measured and adjusted by empirical means, i.e. by testing and experimentation on the locomotive. Even locomotives within the same class could exhibit differences in performance.

A simplified description of a steam locomotive is provided below to help understand some of the key basics of its operation.

As indicated above, the steam locomotive is a heat engine which converts fuel (coal, wood, oil, etc.) to heat; this is then used to do work by driving the pistons to turn the wheels. The operation of a steam locomotive can be thought of in terms of the following broadly defined components:

- Boiler and Fire (Heat conversion)

- Cylinder (Work done)

8.4.1.2.1. Boiler and Fire (Heat conversion)¶

The amount of work that a locomotive can do will be determined by the amount of steam that can be produced (evaporated) by the boiler.

Boiler steam production is typically dependent upon the Grate Area, and the Boiler Evaporation Area.

- Grate Area – the amount of heat energy released by the burning of the fuel is dependent upon the size of the grate area, draught of air flowing across the grate to support fuel combustion, fuel calorific value, and the amount of fuel that can be fed to the fire (a human fireman can only shovel so much coal in an hour). Some locomotives may have had good sized grate areas, but were ‘poor steamers’ because they had small draught capabilities.

- Boiler Evaporation Area – consisted of the part of the firebox in contact with the boiler and the heat tubes running through the boiler. This area determined the amount of heat that could be transferred to the water in the boiler. As a rule of thumb a boiler could produce approximately 12-15 lbs/h of steam per ft2 of evaporation area.

- Boiler Superheater Area – Typically modern steam locomotives are superheated, whereas older locomotives used only saturated steam. Superheating is the process of putting more heat into the steam without changing the pressure. This provided more energy in the steam and allowed the locomotive to produce more work, but with a reduction in steam and fuel usage. In other words a superheated locomotive tended to be more efficient then a saturated locomotive.

8.4.1.2.2. Cylinder (Work done)¶

To drive the locomotive forward, steam was injected into the cylinder which pushed the piston backwards and forwards, and this in turn rotated the drive wheels of the locomotive. Typically the larger the drive wheels, the faster the locomotive was able to travel.

The faster the locomotive travelled the more steam that was needed to drive the cylinders. The steam able to be produced by the boiler was typically limited to a finite value depending upon the design of the boiler. In addition the ability to inject and exhaust steam from the cylinder also tended to reach finite limits as well. These factors typically combined to place limits on the power of a locomotive depending upon the design factors used.

8.4.1.3. Locomotive Types¶

During the course of their development, many different types of locomotives were developed, some of the more common categories are as follows:

- Simple – simple locomotives had only a single expansion cycle in the cylinder

- Compound – locomotives had multiple steam expansion cycles and typically had a high and low pressure cylinder.

- Saturated – steam was heated to only just above the boiling point of water.

- Superheated – steam was heated well above the boiling point of water, and therefore was able to generate more work in the locomotive.

- Geared – locomotives were geared to increase the tractive effort produced by the locomotive, this however reduced the speed of operation of the locomotive.

8.4.1.3.1. Superheated Locomotives¶

In the early 1900s, superheaters were fitted to some locomotives. As the name was implied a superheater was designed to raise the steam temperature well above the normal saturated steam temperature. This had a number of benefits for locomotive engineers in that it eliminated condensation of the steam in the cylinder, thus reducing the amount of steam required to produce the same amount of work in the cylinders. This resulted in reduced water and coal consumption in the locomotive, and generally improved the efficiency of the locomotive.

Superheating was achieved by installing a superheater element that effectively increased the heating area of the locomotive.

8.4.1.3.2. Geared Locomotives¶

In industrial type railways, such as those used in the logging industry, spurs to coal mines were often built to very cheap standards. As a consequence, depending upon the terrain, they were often laid with sharp curves and steep gradients compared to normal main line standards.

Typical main line rod type locomotives couldn’t be used on these lines due to their long fixed wheelbase (coupled wheels) and their relatively low tractive effort was no match for the steep gradients. Thus geared locomotives found their niche in railway practice.

Geared locomotives typically used bogie wheelsets, which allowed the rigid wheelbase to be reduced compared to that of rod type locomotives, thus allowing the negotiation of tight curves. In addition the gearing allowed an increase of their tractive effort to handle the steeper gradients compared to main line tracks.

Whilst the gearing allowed more tractive effort to be produced, it also meant that the maximum piston speed was reached at a lower track speed.

As suggested above, the maximum track speed would depend upon loads and track conditions. As these types of lines were lightly laid, excessive speeds could result in derailments, etc.

The three principal types of geared locomotives used were:

- Shay Locomotives

- Climax

- Heisler

8.4.2. Steam Locomotive Operation¶

To successfully drive a steam locomotive it is necessary to consider the performance of the following elements:

- Boiler and Fire (Heat conversion )

- Cylinder (Work done)

For more details on these elements, refer to the “Elements of Steam Locomotive Operation”

Summary of Driving Tips

- Wherever possible, when running normally, have the regulator at 100%, and use the reverser to adjust steam usage and speed.

- Avoid jerky movements when starting or running the locomotive, thus reducing the chances of breaking couplers.

- When starting always have the reverser fully wound up, and open the regulator slowly and smoothly, without slipping the wheels.

8.4.2.1. Open Rails Steam Functionality (Fireman)¶

The Open Rails Steam locomotive functionality provides two operational options:

- Automatic Fireman (Computer Controlled): In Automatic or Computer Controlled Fireman mode all locomotive firing and boiler management is done by Open Rails, leaving the player to concentrate on driving the locomotive. Only the basic controls such as the regulator and throttle are available to the player.

- Manual Fireman: In Manual Fireman mode all locomotive firing and boiler management must be done by the player. All of the boiler management and firing controls, such as blower, injector, fuel rate, are available to the player, and can be adjusted accordingly.

A full listing of the keyboard controls for use when in manual mode is provided on the Keyboard tab of the Open Rails Options panel.

Use the keys <Crtl+F> to switch between Manual and Automatic firing

modes.

8.4.2.2. Hot or Cold Start¶

The locomotive can be started either in a hot or cold mode. Hot mode simulates a locomotive which has a full head of steam and is ready for duty.

Cold mode simulates a locomotive that has only just had the fire raised, and still needs to build up to full boiler pressure, before having full power available.

This function can be selected through the Open Rails options menu on the Simulation tab.

8.4.2.3. Main Steam Locomotive Controls¶

This section will describe the control and management of the steam locomotive based upon the assumption that the Automatic fireman is engaged. The following controls are those typically used by the driver in this mode of operation:

- Cylinder Cocks – allows water condensation to be exhausted from the

cylinders.

(Open Rails Keys: toggle

<C>) - Regulator – controls the pressure of the steam injected into the

cylinders.

(Open Rails Keys:

<D>= increase,<A>= decrease) - Reverser – controls the valve gear and when the steam is “cutoff”.

Typically it is expressed as a fraction of the cylinder stroke.

(Open Rails Keys:

<W>= increase,<S>= decrease). Continued operation of the W or S key will eventually reverse the direction of travel for the locomotive. - Brake – controls the operation of the brakes.

(Open Rails Keys:

<'>= increase,<;>= decrease)

8.4.2.3.1. Recommended Option Settings¶

For added realism of the performance of the steam locomotive, it is suggested that the following settings be considered for selection in the Open Rails options menu:

- Break couplers

- Curve speed dependent

- Curve resistance speed

- Hot start

- Tunnel resistance dependent

NB: Refer to the relevant sections of the manual for more detailed description of these functions.

8.4.2.3.2. Locomotive Starting¶

Open the cylinder cocks. They are to remain open until the engine has traversed a distance of about an average train length, consistent with safety.

The locomotive should always be started in full gear (reverser up as high as possible), according to the direction of travel, and kept there for the first few turns of the driving wheels, before adjusting the reverser.

After ensuring that all brakes are released, open the regulator sufficiently to move the train, care should be exercised to prevent slipping; do not open the regulator too much before the locomotive has gathered speed. Severe slipping causes excessive wear and tear on the locomotive, disturbance of the fire bed and blanketing of the spark arrestor. If slipping does occur, the regulator should be closed as appropriate, and if necessary sand applied.

Also, when starting, a slow even increase of power will allow the couplers all along the train to be gradually extended, and therefore reduce the risk of coupler breakages.

8.4.2.3.3. Locomotive Running¶

Theoretically, when running, the regulator should always be fully open and the speed of the locomotive controlled, as desired, by the reverser. For economical use of steam, it is also desirable to operate at the lowest cut-off values as possible, so the reverser should be operated at low values, especially running at high speeds.

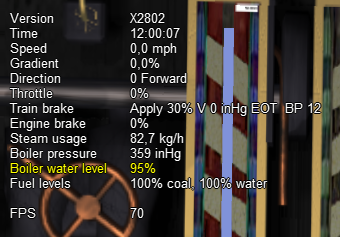

When running a steam locomotive keep an eye on the following key

parameters in the Heads up Display (HUD – <F5>) as they will give the driver

an indication of the current status and performance of the locomotive with

regard to the heat conversion (Boiler and Fire) and work done (Cylinder)

processes. Also bear in mind the above driving tips.

- Direction – indicates the setting on the reverser and the direction of travel. The value is in per cent, so for example a value of 50 indicates that the cylinder is cutting off at 0.5 of the stroke.

- Throttle – indicates the setting of the regulator in per cent.

- Steam usage – these values represent the current steam usage per hour.

- Boiler Pressure – this should be maintained close to the maximum working pressure of the locomotive.

- Boiler water level – indicates the level of water in the boiler. Under operation in Automatic Fireman mode, the fireman should manage this.

- Fuel levels – indicate the coal and water levels of the locomotive.

For information on the other parameters, such as the brakes, refer to the relevant sections in the manual.

For the driver of the locomotive the first two steam parameters are the key ones to focus on, as operating the locomotive for extended periods of time with steam usage in excess of the steam generation value will result in declining boiler pressure. If this is allowed to continue the locomotive will ultimately lose boiler pressure, and will no longer be able to continue to pull its load.

Steam usage will increase with the speed of the locomotive, so the driver will need to adjust the regulator, reverser, and speed of the locomotive to ensure that optimal steam pressure is maintained. However, a point will finally be reached where the locomotive cannot go any faster without the steam usage exceeding the steam generation. This point determines the maximum speed of the locomotive and will vary depending upon load and track conditions

The AI Fireman in Open Rails is not proactive, ie it cannot look ahead for gradients, etc, and therefore will only add fuel to the fire once the train is on the gradient. This reactive approach can result in a boiler pressure drop whilst the fire is building up. Similarly if the steam usage is dropped (due to a throttle decrease, such as approaching a station) then the fire takes time to reduce in heat, thus the boiler pressure can become excessive.

To give the player a little bit more control over this, and to facilitate the maintaining of the boiler pressure the following key controls have been added to the AI Fireman function:

AIFireOn - (<Alt+H>) - Forces the AI fireman to start building

the fire up (increases boiler heat & pressure, etc) - typically used just

before leaving a station to maintain pressure as steam consumption increases.

This function will be turned off if AIFireOff, AIFireReset are triggered or

if boiler pressure or BoilerHeat exceeds the boiler limit.

AIFireOff - (<Ctrl+H>) - Forces the AI fireman to stop adding

to the fire (allows boiler heat to decrease as fire drops) - typically used

approaching a station to allow the fire heat to decrease, and thus stopping

boiler pressure from exceeding the maximum. This function will be turned off

if AIFireOn, AIFireReset are triggered or if boiler pressure or BoilerHeat

drops too low.

AIFireReset - (<Ctrl+Alt+H>) - turns off both of the above

functions when desired.

If theses controls are not used, then the AI fireman operates in the same fashion as previously.

8.4.2.4. Steam Locomotive Carriage Steam Heat Modelling¶

8.4.2.4.1. Overview¶

In the early days of steam, passenger carriages were heated by fire burnt in stoves within the carriage, but this type of heating proved to be dangerous, as on a number of occasions the carriages actually caught fire and burnt.

A number of alternative heating systems were adopted as a safer replacement.

The Open Rails Model is based upon a direct steam model, ie one that has steam pipes installed in each carriage, and pumps steam into each car to raise the internal temperature in each car.

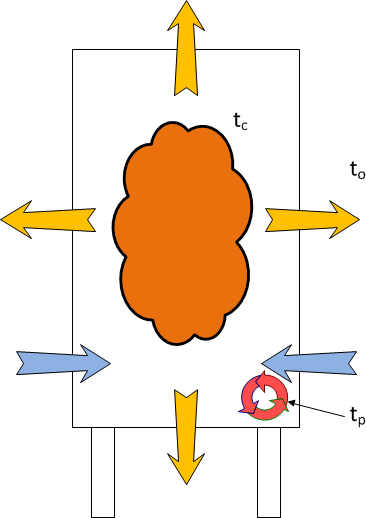

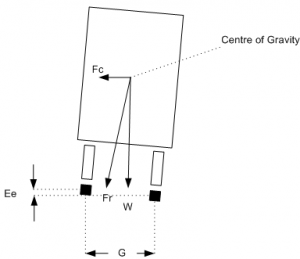

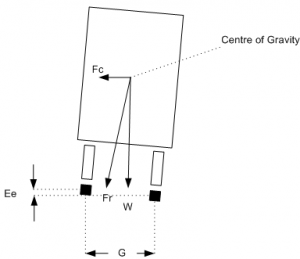

The heat model in each car is represented by Figure 1 below. The key parameters influencing the operation of the model are the values of tc, to, tp, which represent the temperature within the carriage, ambient temperature outside the carriage, and the temperature of the steam pipe due to steam passing through it.

As shown in the figure the heat model has a number of different elements as follows:

- Internal heat mass – the air mass in the carriage (represented by cloud) is heated to temperature that is comfortable to the passengers. The energy required to maintain the temperature will be determined the volume of the air in the carriage

- Heat Loss – Transmission – over time heat will be lost through the walls, roof, and floors of the carriage (represented by outgoing orange arrows), this heat loss will reduce the temperature of the internal air mass.

- Heat Loss – Infiltration – also over time as carriage doors are opened and closed at station stops, some cooler air will enter the carriage (represented by ingoing blue arrows), and reduce the temperature of the internal air mass.

- Steam Heating – to offset the above heat losses, steam was piped through each of the carriages (represented by circular red arrows). Depending upon the heat input from the steam pipe, the temperature would be balanced by offsetting the steam heating against the heat losses.

8.4.2.4.2. Carriage Heating Implementation in Open Rails¶

Currently, carriage steam heating is only available on steam locomotives. To enable steam heating to work in Open Rails the following parameter must be included in the engine section of the steam locomotive ENG File:

MaxSteamHeatingPressure( x )

Where: x = maximum steam pressure in the heating pipe – should not exceed 100 psi

If the above parameter is added to the locomotive, then an extra line will appear in the extended HUD to show the temperature in the train, and the steam heating pipe pressure, etc.

Steam heating will only work if there are passenger cars attached to the locomotive.

Warning messages will be displayed if the temperature inside the carriage goes outside of the limits of 10–15.5°C.

The player can control the train temperature by using the following controls:

<Alt+U>– increase steam pipe pressure (and hence train temperature)<Alt+D>– decrease steam pipe pressure (and hence train temperature)

The steam heating control valve can be configured by adding an enginecontroller

called ORTSSTeamHeat ( w, x, y, z). It should be configured as a standard

4 value controller.

It should be noted that the impact of steam heating will vary depending upon the season, length of train, etc.

8.4.3. Steam Locomotives – Physics Parameters for Optimal Operation¶

8.4.3.1. Required Input ENG and WAG File Parameters¶

The OR Steam Locomotive Model (SLM) should work with default MSTS files; however optimal performance will only be achieved if the following settings are applied within the ENG file. The following list only describes the parameters associated with the SLM, other parameters such as brakes, lights, etc. still need to be included in the file. As always, make sure that you keep a backup of the original MSTS file.

Open Rails has been designed to do most of the calculations for the modeler, and typically only the key parameters are required to be included in the ENG or WAG file. The parameters shown in the Locomotive performance Adjustments section should be included only where a specific performance outcome is required, since default parameters should provide a satisfactory result.

When creating and adjusting ENG or WAG files, a series of tests should be undertaken to ensure that the performance matches the actual real-world locomotive as closely as possible. For further information on testing, as well as some suggested test tools, go to this site.

NB: These parameters are subject to change as Open Rails continues to develop.

Notes:

- New – parameter names starting with ORTS means added as part of OpenRails development

- Existing – parameter names not starting with ORTS are original in MSTS or added through MSTS BIN

Possible Locomotive Reference Info:

- Steam Locomotive Data

- Example Wiki Locomotive Data

- Testing Resources for Open Rails Steam Locomotives

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Units | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Information (Engine section) | |||

| ORTSSteamLocomotiveType ( x ) | Describes the type of locomotive | Simple, Compound, Geared | (Simple)

(Compound)

(Geared)

|

| WheelRadius ( x ) | Radius of drive wheels | Distance | (0.648m)

(36in)

|

| MaxSteamHeatingPressure ( x ) | Max pressure in steam heating system for passenger carriages | Pressure, NB: normally < 100 psi | (80psi) |

| Boiler Parameters (Engine section) | |||

| ORTSSteamBoilerType ( x ) | Describes the type of boiler | Saturated, Superheated | (Saturated)

(Superheated)

|

| BoilerVolume ( x ) | Volume of boiler. This parameter is not overly critical. | Volume, where an act. value is n/a, use approx. EvapArea / 8.3 | (“220*(ft^3)”) (“110*(m^3)”) |

| ORTSEvaporationArea ( x ) | Boiler evaporation area | Area | (“2198*(ft^2)”) (“194*(m^2)”) |

| MaxBoilerPressure ( x ) | Max boiler working pressure (gauge) | Pressure | (200psi)

(200kPa)

|

| ORTSSuperheatArea ( x ) | Superheating heating area | Area | (“2198*(ft^2)”) (“194*(m^2)” ) |

| Locomotive Tender Info (Engine section) | |||

| MaxTenderWaterMass ( x ) | Water in tender | Mass | (36500lb)

(16000kg)

|

| MaxTenderCoalMass ( x ) | Coal in tender | Mass | (13440lb)

(6000kg)

|

| IsTenderRequired ( x ) | Locomotive Requires a tender | 0 = No, 1 = Yes | (0)

(1)

|

| Fire (Engine section) | |||

| ORTSGrateArea ( x ) | Locomotive fire grate area | Area | (“2198*(ft^2)”) (“194*(m^2)”) |

| ORTSFuelCalorific ( x ) | Calorific value of fuel | For coal use 13700 btu/lb | (13700btu/lb) (33400kj/kg) |

| ORTSSteamFiremanMaxPossibleFiringRate ( x ) | Maximum fuel rate that fireman can shovel in an hour. (Mass Flow) | Use as def: UK:3000lb/h US:5000lb/h AU:4200lb/h | (4200lb/h) (2000kg/h) |

| SteamFiremanIsMechanicalStoker ( x ) | Mechanical stoker = large rate of coal feed | Boolean, 0=no-stoker 1=stoker | ( 1 ) |

| Steam Cylinder (Engine section) | |||

| NumCylinders ( x ) | Number of steam cylinders | Boolean | ( 2 ) |

| CylinderStroke ( x ) | Length of cylinder stroke | Distance | (26in)

(0.8m)

|

| CylinderDiameter ( x ) | Cylinder diameter | Distance | (21in)

(0.6m)

|

| LPNumCylinders ( x ) | Number of steam LP cylinders (compound locomotive only) | Boolean | ( 2 ) |

| LPCylinderStroke ( x ) | LP cylinder stroke length (compound locomotive only) | Distance | (26in)

(0.8m)

|

| LPCylinderDiameter ( x ) | Diameter of LP cylinder (compound locomotive only) | Distance | (21in)

(0.6m)

|

| Friction (Wagon section) | |||

| ORTSDavis_A ( x ) | Journal or roller bearing + mechanical friction | N, lbf. Use FCalc to calculate | (502.8N)

(502.8lb)

|

| ORTSDavis_B ( x ) | Flange friction | Nm/s, lbf/mph. Use FCalc | (1.5465Nm/s) (1.5465lbf/mph) |

| ORTSDavis_C ( x ) | Air resistance friction | Nm/s^2, lbf/mph^2 Use FCalc | (1.43Nm/s^2) (1.43lbf/mph^2) |

| ORTSBearingType ( x ) | Bearing type, defaults to Friction | Roller,

Friction,

Low

|

( Roller ) |

| Friction (Engine section) | |||

| ORTSDriveWheelWeight ( x ) | Total weight on the locomotive driving wheels | Mass, Leave out if unknown | (2.12t) |

| Curve Speed Limit (Wagon section) | |||

| ORTSUnbalancedSuperElevation ( x ) | Determines the amount of Cant Deficiency applied to carriage | Distance, Leave out if unknown | (3in) (0.075m) |

| ORTSTrackGauge( x ) | Track gauge | Distance, Leave out if unknown | (4ft 8.5in)

( 1.435m )

( 4.708ft)

|

| CentreOfGravity ( x, y, z ) | Defines the centre of gravity of a locomotive or wagon | Distance, Leave out if unknown | (0m, 1.8m, 0m)

(0ft, 5.0ft, 0ft)

|

| Curve Friction (Wagon section) | |||

| ORTSRigidWheelBase ( x ) | Rigid wheel base of vehicle | Distance, Leave out if unknown | (5ft 6in)

(3.37m)

|

| Locomotive Gearing (Engine section – Only required if locomotive is geared) | |||

| ORTSSteamGearRatio ( a, b ) | Ratio of gears | Numeric | (2.55, 0.0) |

| ORTSSteamMaxGearPistonRate ( x ) | Max speed of piston | ft/min | ( 650 ) |

| ORTSSteamGearType ( x ) | Fixed gearing or selectable gearing | Fixed, Select | (Fixed)

(Select)

|

| Locomotive Performance Adjustments (Engine section – Optional, for experienced modellers) | |||

| ORTSBoilerEvaporationRate ( x ) | Multipl. factor for adjusting maximum boiler steam output | Be tween 10–15, Leave out if not used | (15.0) |

| ORTSBurnRate ( x, y ) | Tabular input: Coal combusted (y) to steam generated (x) | x – lbs, y – kg, series of x & y values. Leave out if unused | |

| ORTSCylinderEfficiencyRate ( x ) | Multipl. factor for steam cylinder (force) output | Un limited, Leave out if unused | (1.0) |

| ORTSBoilerEfficiency (x, y) | Tabular input: boiler efficiency (y) to coal combustion (x) | x – lbs/ft2/h, series of x & y values. Leave out if unused | |

| ORTSCylinderExhaustOpen ( x ) | Point at which the cylinder exhaust port opens | Between 0.1–0.95, Leave out if unused | (0.1) |

| ORTSCylinderPortOpening ( x ) | Size of cylinder port opening | Between 0.05–0.12, Leave out if unused | (0.085) |

| ORTSCylinderInitialPressureDrop ( x, y ) | Tabular input: wheel speed (x) to pressure drop factor (y) | x – rpm, series of x & y values. Leave out if unused | |

| ORTSCylinderBackPressure ( x, y ) | Tabular input: Loco indicated power (x) to backpressure (y) | x – hp, y – psi(g), series of x & y values. Leave out if unused | |

8.4.4. Special Visual Effects for Locomotives or Wagons¶

Steam exhausts on a steam locomotive, and other special visual effects can be modelled in OR by defining

appropriate visual effects in the SteamSpecialEffects section of the steam locomotive ENG file, the

DieselSpecialEffects section of the diesel locomotive ENG file, or the SpecialEffects section

of a relevant wagon (including diesel, steam or electric locomotives.

OR supports the following special visual effects in a steam locomotive:

- Steam cylinders (named

CylindersFXandCylinders2FX) – two effects are provided which will represent the steam exhausted when the steam cylinder cocks are opened. Two effects are provided to represent the steam exhausted at the front and rear of each piston stroke. These effects will appear whenever the cylinder cocks are opened, and there is sufficient steam pressure at the cylinder to cause the steam to exhaust, typically the regulator is open (> 0%). - Stack (named

StackFX) – represents the smoke stack emissions. This effect will appear all the time in different forms depending upon the firing and steaming conditions of the locomotive. - Compressor (named

CompressorFX) – represents a steam leak from the air compressor. Will only appear when the compressor is operating. - Generator (named

GeneratorFX) – represents the emission from the turbo-generator of the locomotive. This effect operates continually. If a turbo-generator is not fitted to the locomotive it is recommended that this effect is left out of the effects section which will ensure that it is not displayed in OR. - Safety valves (named

SafetyValvesFX) – represents the discharge of the steam valves if the maximum boiler pressure is exceeded. It will appear whenever the safety valve operates. - Whistle (named

WhistleFX) – represents the steam discharge from the whistle. - Injectors (named

Injectors1FXandInjectors2FX) – represents the steam discharge from the steam overflow pipe of the injectors. They will appear whenever the respective injectors operate.

OR supports the following special visual effects in a diesel locomotive:

- Exhaust (named

Exhaustnumber) – is a diesel exhaust. Multiple exhausts can be defined, simply by adjusting the numerical value of the number after the key word exhaust.

OR supports the following special visual effects in a wagon (also the wagon section of an ENG file):

- Steam Heating Boiler (named

HeatingSteamBoilerFX) – represents the exhaust for a steam heating boiler. Typically this will be set up on a diesel or electric train as steam heating was provided directly from a steam locomotive. - Wagon Generator (named

WagonGeneratorFX) – represents the exhaust for a generator. This generator was used to provide additional auxiliary power for the train, and could have been used for air conditioning, heating lighting, etc. - Wagon Smoke (named

WagonSmokeFX) – represents the smoke coming from say a wood fire. This might have been a heating unit located in the guards van of the train. - Heating Hose (named

HeatingHoseFX) – represents the steam escaping from a steam pipe connection between wagons.

NB: If a steam effect is not defined in the SteamSpecialEffects, DieselSpecialEffects, or the

SpecialEffects section of an ENG/WAG file, then it will not be displayed in the simulation.

Similarly if any of the co-ordinates are zero, then the effect will not be displayed.

Each effect is defined by inserting a code block into the ENG/WAG file similar to the one shown below:

CylindersFX (

-1.0485 1.0 2.8

-1 0 0

0.1

)

The code block consists of the following elements:

- Effect name – as described above,

- Effect location on the locomotive (given as an x, y, z offset in metres from the origin of the wagon shape)

- Effect direction of emission (given as a normal x, y and z)

- Effect nozzle width (in metres)

8.4.5. Auxiliary Water Tenders¶

To increase the water carrying capacity of a steam locomotive, an auxiliary tender (or as known in Australia as a water gin) would sometimes be coupled to the locomotive. This auxiliary tender would provide additional water to the locomotive tender via connecting pipes.

Typically, if the connecting pipes were opened between the locomotive tender and the auxiliary tender, the water level in the two vehicles would equalise at the same height.

To implement this feature in Open Rails, a suitable water carrying vehicle needs to have the following parameter included in the WAG file.

ORTSAuxTenderWaterMass ( 70000lb ) The units of measure are in mass.

When the auxiliary tender is coupled to the locomotive the tender line in the LOCOMOTIVE INFORMATION HUD will show the two tenders and the water capacity of each. Water (C) is the combined water capacity of the two tenders, whilst Water (T) shows the water capacity of the locomotive tender, and Water (A) the capacity of the auxiliary tender (as shown below).

To allow the auxiliary tender to be filled at a water fuelling point, a water freight animation will be need to be added to the WAG file as well. (Refer to Freight Animations for more details).

8.5. Engines – Multiple Units in Same Consist or AI Engines¶

In an OR player train one locomotive is controlled by the player, while the other units are controlled by default by the train’s MU (multiple unit) signals for braking and throttle position, etc. The player-controlled locomotive generates the MU signals which are passed along to every unit in the train. For AI trains, the AI software directly generates the MU signals, i.e. there is no player-controlled locomotive. In this way, all engines use the same physics code for power and friction.

This software model will ensure that non-player controlled engines will behave exactly the same way as player controlled ones.

8.6. Open Rails Braking¶

Open Rails software has implemented its own braking physics in the current release. It is based on the Westinghouse 26C and 26F air brake and controller system. Open Rails braking will parse the type of braking from the .eng file to determine if the braking physics uses passenger or freight standards, self-lapping or not. This is controlled within the Options menu as shown in General Options above.

Selecting Graduated Release Air Brakes in Menu > Options allows partial release of the brakes. Some 26C brake valves have a cut-off valve that has three positions: passenger, freight and cut-out. Checked is equivalent to passenger standard and unchecked is equivalent to freight standard.

The Graduated Release Air Brakes option controls two different features. If the train brake controller has a self-lapping notch and the Graduated Release Air Brakes box is checked, then the amount of brake pressure can be adjusted up or down by changing the control in this notch. If the Graduated Release Air Brakes option is not checked, then the brakes can only be increased in this notch and one of the release positions is required to release the brakes.

Another capability controlled by the Graduated Release Air Brakes checkbox is the behavior of the brakes on each car in the train. If the Graduated Release Air Brakes box is checked, then the brake cylinder pressure is regulated to keep it proportional to the difference between the emergency reservoir pressure and the brake pipe pressure. If the Graduated Release Air Brakes box is not checked and the brake pipe pressure rises above the auxiliary reservoir pressure, then the brake cylinder pressure is released completely at a rate determined by the retainer setting.

The following brake types are implemented in OR:

- Vacuum single

- Air single-pipe

- Air twin-pipe

- EP (Electro-pneumatic)

- Single-transfer-pipe (air and vacuum)

The operation of air single-pipe brakes is described in general below.

The auxiliary reservoir needs to be charged by the brake pipe and, depending on the WAG file parameters setting, this can delay the brake release. When the Graduated Release Air Brakes box is not checked, the auxiliary reservoir is also charged by the emergency reservoir (until both are equal and then both are charged from the pipe). When the Graduated Release Air Brakes box is checked, the auxiliary reservoir is only charged from the brake pipe. The Open Rails software implements it this way because the emergency reservoir is used as the source of the reference pressure for regulating the brake cylinder pressure.

The end result is that you will get a slower release when the Graduated Release Air Brakes box is checked. This should not be an issue with two pipe air brake systems because the second pipe can be the source of air for charging the auxiliary reservoirs.

Open Rails software has modeled most of this graduated release car brake behavior based on the 26F control valve, but this valve is designed for use on locomotives. The valve uses a control reservoir to maintain the reference pressure and Open Rails software simply replaced the control reservoir with the emergency reservoir.

Increasing the Brake Pipe Charging Rate (psi/s) value controls the charging rate. Increasing the value will reduce the time required to recharge the train; while decreasing the value will slow the charging rate. However, this might be limited by the train brake controller parameter settings in the ENG file. The brake pipe pressure cannot go up faster than that of the equalization reservoir.

The default value, 21, should cause the recharge time from a full set to be about 1 minute for every 12 cars. If the Brake Pipe Charging Rate (psi/s) value is set to 1000, the pipe pressure gradient features will be disabled and will also disable some but not all of the other new brake features.

Brake system charging time depends on the train length as it should, but at the moment there is no modeling of main reservoirs and compressors.

8.6.1. Brake Shoe Adhesion¶

The braking of a train is impacted by the following two types of adhesion (friction coefficients):

- Brakeshoe – the coefficient of friction of the brakeshoe varies due to the type of brake shoe, and the speed of the wheel increases. Typically older cast iron brake shoes had lower friction coefficients then more modern composite brakeshoes.

- Wheel – the adhesion or friction coefficient between the wheel and the rail will also vary with different conditions, such as whether the track was dry or wet, and will also vary with the speed of rotation of the wheel.

Thus a train traveling at high speed will have lower brake shoe adhesion, which means that the train will take a longer time to stop (or alternatively more force needs to be applied to the brakeshoe to achieve the same slowing effect of the wheel, as at slower speeds). Traveling at high speeds may also result in insufficient force being available to stop the train, and therefore under some circumstances the train may become uncontrollable (unstoppable) or runaway on steep falling gradients.

Conversely if too much force is applied to the brakeshoe, then the wheel could lock up, and this could result in the wheel slipping along the rail once the adhesive force (wagon weight x coefficient of friction) of the wagon is exceeded by the braking force. In this instance the static friction between the wheel and the track will change to dynamic friction, which is significantly lower than the static friction, and thus the train will not be stopped in the desired time and distance.

When designing the braking forces railway engineers need to ensure that the maximum braking force applied to the wheels takes into account the above adhesion factors.

Implementation in Open Rails

Open Rails models the aspects described above, and operates within one of the following modes:

- Advanced Adhesion NOT selected - brake force operates as per previous OR functionality, i.e. - constant brake force regardless of speed.

- Advanced Adhesion SELECTED and legacy WAG files, or NO additional user friction data defined in WAG file - OR assumes the users assigned friction coefficient have been set at 20% friction coefficient for cast iron brakes, and reverse engineers the braking force, and then applies the default friction curve as the speed varies.

- Advanced Adhesion SELECTED and additional user friction data HAS been defined in WAG file - OR applies the user defined friction/speed curve.

It should be noted that the MaxBrakeForce parameter in the WAG file is the actual force applied to the wheel after reduction by the friction coefficient.

Option iii) above is the ideal recommended method of operating, and naturally will require include files, or variations to the WAG file.

To setup the WAG file, the following values need to be set:

- use the OR parameter

ORTSBrakeShoeFriction ( x, y )to define an appropriate friction/speed curve, where x = speed in kph, and y = brakeshoe friction. This parameter needs to be included in the WAG file near the section defining the brakes. This parameter allows the user to customise to any brake type. - Define the

MaxBrakeForcevalue with a friction value equal to the zero speed value of the above curve, i.e. in the case of the curve below this woyuld be 0.49.

For example, a sample curve definition for a COBRA (COmposition BRAkes) brakeshoe might be as follows:

ORTSBrakeShoeFriction ( 0.0 0.49 8.0 ................ 80.5 0.298 88.5 0.295 96.6 0.289 104.6 0.288 )

The debug FORCES INFORMATION HUD has been modified by the addition of two extra columns:

- Brk. Frict. - Column shows the current friction value of the brakeshoe and will vary according to the speed. (Applies to modes ii) and iii) above). In mode i) it will show friction constant at 100%, which indicates that the MaxBrakeForce defined in the WAG file is being used without alteration, ie it is constant regardless of the speed.

- Brk. Slide - indicates that the vehicle wheels are sliding along the track under brake application. (Ref to Wheel Skidding due to Excessive Brake Force )

It should be noted that the Adhesion factor correction slider in the options menu will vary the brakeshoe coefficient above and below 100% (or unity). It is recommended that this is set @ the default value of 100%.

These changes introduce an extra challenge to train braking, but provide a more realistic train operation.

For example, in a lot of normal Westinghouse brake systems, a minimum pressure reduction was applied by moving the brake controller to the LAP position. Typically Westinghouse recommended values of between 7 and 10 psi.

8.6.2. Train Brake Pipe Losses¶

The train brake pipe on a train is subject to air losses through leakage at joints, etc. Typically when the brake controller is in the RUNNING position, air pressure is maintained in the pipe from the reservoir. However on some brake systems, especially older ones such as the A6-ET, when the brake controller is in the LAP position the train brkae pipe is isolated from the air reservoir, and hence over time the pipe will suffer pressure drops due to leakages. This will result in the brakes being gradually applied.

More modern brake systems have a self lapping feature which compensates for train brake pipe leakage regardless of the position that the brake controller is in.

Open Rails models this feature whenever the TrainPipeLeakRate parameter is defined in the engine section of the ENG file. Typically most railway companies accepted leakage rates of around 5 psi/min in the train brake pipe before some remedial action needed to be undertaken.

If this parameter is left out of the ENG file, then no leakage will occur.

8.6.3. Wheel Skidding due to Excessive Brake Force¶

The application of excessive braking force onto a wheel can cause it to lock up and then start to slip along the rails. This occurs where the wagon braking force exceeds the adhesive weight force of the wagon wheel, i.e. the wheel to rail friction is overcome, and the wheel no longer grips the rails.

Typically this happens with lightly loaded vehicles at lower speeds, and hence the need to ensure that braking forces are applied to design standards. Skidding will be more likely to occur when the adhesion between the wheel and track is low, so for example skidding is more likely in wet weather then dry weather. The value Wag Adhesion in the FORCES INFORMATION HUD indicates this adhesion value, and will vary with the relevant weather conditions.

When a vehicle experiences wheel skid, an indication is provided in the FORCES INFORMATION HUD. To correct the problem the brakes must be released, and then applied slowly to ensure that the wheels are not locked up. Wheel skid will only occur if ADVANCED adhesion is selected in the options menu.

(Ref to Wheel Skidding due to Excessive Brake Force for additional information)

8.6.4. Using the F5 HUD Expanded Braking Information¶

This helps users of Open Rails to understand the status of braking within the game and assists in realistically coupling and uncoupling cars. Open Rails braking physics is more realistic than MSTS, as it models the connection, charging and exhaust of brake lines.

When coupling to a static consist, note that the brake line for the newly added cars normally does not have any pressure. This is because the train brake line/hose has not yet been connected. The last columns of each line shows the condition of the air brake hose connections of each unit in the consist.

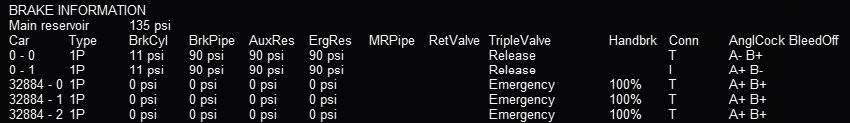

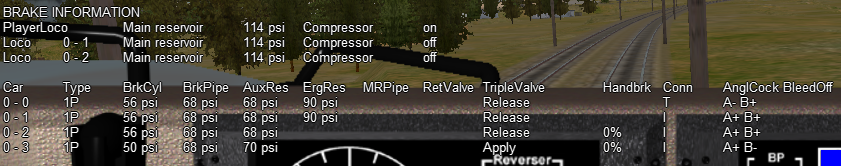

The columns under AnglCock describe the state of the Angle Cock, a

manually operated valve in each of the brake hoses of a car: A is the

cock at the front, B is the cock at the rear of the car. The symbol +

indicates that the cock is open and the symbol - that it is closed. The

column headed by T indicates if the hose on the locomotive or car is

interconnected: T means that there is no connection, I means it is

connected to the air pressure line. If the angle cocks of two consecutive

cars are B+ and A+ respectively, they will pass the main air hose

pressure between the two cars. In this example note that the locomotive

air brake lines start with A- (closed) and end with B- (closed) before

the air hoses are connected to the newly coupled cars. All of the newly

coupled cars in this example have their angle cocks open, including those

at the ends, so their brake pressures are zero. This will be reported as

Emergency state.

8.6.4.1. Coupling Cars¶

Also note that, immediately after coupling, you may also find that the

handbrakes of the newly added cars have their handbrakes set to 100% (see

column headed Handbrk). Pressing <Shift+;> (Shift plus semicolon

in English keyboards) will release all the handbrakes on the consist as

shown below. Pressing <Shift+'> (Shift plus apostrophe on English

keyboards) will set all of the handbrakes. Cars without handbrakes will

not have an entry in the handbrake column.

If the newly coupled cars are to be moved without using their air brakes and parked nearby, the brake pressure in their air hose may be left at zero: i.e. their hoses are not connected to the train’s air hose. Before the cars are uncoupled in their new location, their handbrakes should be set. The cars will continue to report State Emergency while coupled to the consist because their BC value is zero; they will not have any braking. The locomotive brakes must be used for braking. If the cars are uncoupled while in motion, they will continue coasting.

If the brakes of the newly connected cars are to be controlled by the

train’s air pressure as part of the consist, their hoses must be joined

together and to the train’s air hose and their angle cocks set correctly.

Pressing the Backslash key <\>) (in English keyboards; please check the

keyboard assignments for other keyboards) connects the brake hoses

between all cars that have been coupled to the engine and sets the

intermediate angle cocks to permit the air pressure to gradually approach

the same pressure in the entire hose. This models the operations

performed by the train crew. The HUD display changes to show the new

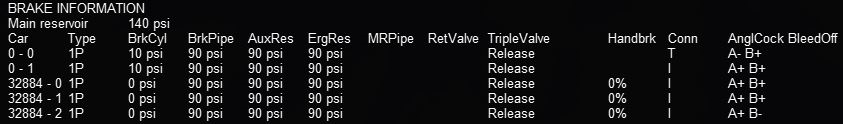

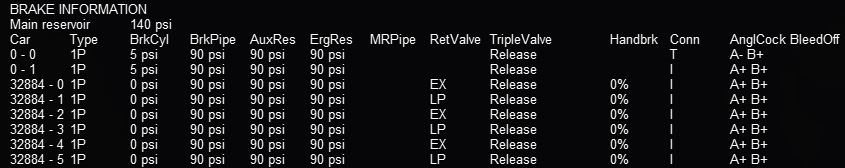

condition of the brake hose connections and angle cocks:

All of the hoses are now connected; only the angle cocks on the lead

locomotive and the last car are closed as indicated by the -. The rest

of the cocks are open (+) and the air hoses are joined together (all

I) to connect to the air supply on the lead locomotive.

Upon connection of the hoses of the new cars, recharging of the train brake line commences. Open Rails uses a default charging rate of about 1 minute per every 12 cars. The HUD display may report that the consist is in Emergency state; this is because the air pressure dropped when the empty car brake systems were connected. Ultimately the brake pressures reach their stable values:

If you don’t want to wait for the train brake line to charge, pressing

<Shift+/> (in English keyboards) executes Brakes Initialize which

will immediately fully charge the train brakes line to the final state.

However, this action is not prototypical and also does not allow control

of the brake retainers.

The state of the angle cocks, the hose connections and the air brake pressure of individual coupled cars can be manipulated by using the F9 Train Operations Monitor, described here. This will permit more realistic shunting of cars in freight yards.

8.6.4.2. Uncoupling Cars¶

When uncoupling cars from a consist, using the F5 HUD Expanded Brake

Display in conjunction with the F9 Train Operations Monitor display

allows the player to set the handbrakes on the cars to be uncoupled, and

to uncouple them without losing the air pressure in the remaining cars.

Before uncoupling, close the angle cock at the rear of the car ahead of

the first car to be uncoupled so that the air pressure in the remaining

consist is not lost when the air hoses to the uncoupled cars are

disconnected. If this procedure is not followed, the train braking system

will go into Emergency state and will require pressing the <\>